Abdullah M. Rafi, Samina Huque

Safeguarding has increasingly become a central concern in public health research. At ARK Foundation, we see it not just as a set of rules, but as a commitment to ensuring the safety and dignity of everyone, spanning from researchers to office staff, across every stage of research. To better understand the intersections of safeguarding and gender, I sat down with our colleague, Senior Project Manager Samina Huque, who also serves as the organization’s Gender and Safeguarding Focal Point.

Safeguarding as Everyday Safety

When asked how she defines safeguarding, she was clear: safeguarding means safety. “The safety of everyone, everywhere – from the field to the office to the home,” she explained. Safety is not just about reacting to incidents, but about being alert beforehand. For example, ARK Foundation never sends a female researcher to the field alone, considering the societal risks that might arise. Field sites, especially outside Dhaka, are unpredictable; situations can quickly change, and conflicts are not always possible to resolve on the spot. “That’s why we prefer to send more than one person, male or female, to any field visit,” she said.

She also noted that safeguarding is not limited to personal harm. Researchers may witness issues like domestic violence or conflict during their work, making it all the more important to be prepared. “The main thing about safeguarding is being alert prior to the work. I can be a victim or an eyewitness,” she emphasized.

Why Gender Matters More Now

Over the last decade, gender has shifted from being a “box to tick” to a crucial dimension of safeguarding. “In the past, gender was hardly prioritized. But in the last five years, it has become very important,” she reflected. Donors and senior researchers are increasingly attentive to the stark differences in how men and women experience health challenges in societies like ours.

She shared an example from her tuberculosis research: a female patient diagnosed with MDR-TB was sent away from her home, barred from seeing her children, and eventually ostracized by her family. In contrast, a male patient in the same hospital described a supportive family and community, with his wife bringing him meals during his treatment. “The disease was the same, but the gendered realities were worlds apart,” she noted.

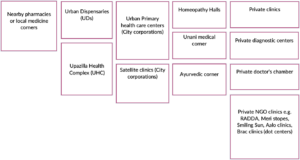

This recognition has changed the way projects are designed. Gender and safeguarding issues are now built into research tools, consent processes, and study protocols. For example, female patients’ reluctance to visit local facilities often stemmed from the fact that most healthcare providers were male. Male patients, meanwhile, cited reasons like lack of time or money. “Understanding these differences is essential if we are to design responsive and inclusive health systems,” she argued.

Common Risks in Research Settings

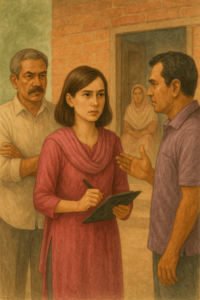

The safeguarding focal point pointed to a number of recurring risks in fieldwork. Women researchers often face harassment or restrictions from male gatekeepers who prevent them from speaking with female participants. Sometimes researchers have even faced aggression from patients, including those with mental health issues. “It’s not just in the field. Even in offices, safeguarding issues arise, like colleagues speaking disrespectfully to one another,” she explained.

ARK’s Approach to Safeguarding

To address these challenges, ARK Foundation has adopted a proactive approach. All field researchers receive training on safeguarding. “We consider our staff as ambassadors of ARK, so professionalism is at the heart of everything,” she said. Training modules cover both sides: researchers as potential victims and researchers as possible sources of safeguarding concerns.

Gender-sensitive practices are also emphasized. Male researchers are trained to approach female participants respectfully and, where necessary, build rapport through family members. Consent forms include contact details of the safeguarding focal point, allowing participants to raise concerns directly.

When Safeguarding Fails

Even with systems in place, problems can occur. She recounted an incident involving a former male colleague who persistently harassed female coworkers, both inside and outside the office. Despite warnings and counseling, the behavior did not stop, and he had to be dismissed. “The surprising thing was that he continued this behavior even after leaving the organization,” she recalled.

The Role of Donors and Ethics Boards

The good news, she noted, is that donors and ethics committees are now prioritizing safeguarding. ARK is required to log safeguarding incidents and report them to donors. “I even received a nine-hour safeguarding training from the University of Leeds, and now we evaluate safeguarding situations annually,” she said. Partner organizations themselves are also beginning to propose safeguarding measures in research cycles.

Looking Ahead

Despite progress, challenges remain. “We still lack proper gender representation in research. We have a long way to go,” she observed. At ARK, efforts are being made to recruit and empower female researchers, from early-career staff to senior positions. Training is designed to build confidence and reinforce equality. But she stressed that this cannot be achieved by institutions alone. “This requires a collaborative approach from donors, research institutions, and all stakeholders.”