While speaking about the strengthening of the health systems, one area where discussions often get stuck is the collaboration among all the parties involved. Now, this point – no matter how simple and straightforward it may seem – is something that continues to slither through the country’s efforts to build a proper health system. Why? Because it takes a whole lot of effort to bring all the stakeholders under one umbrella.

Despite its own set of drawbacks and realities, the rural health system in Bangladesh operates in a relatively more coordinated manner than the urban one. Both the patients and service providers (including doctors and allied health workforce) are generally aware of their roles and the designated points of service delivery in a rural setting. But when it comes to the urban health sector— things start to get complicated. It’s managed and run by a plethora of actors. Alongside the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare (MoHFW), there are a number of other government bodies including the Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development & Cooperatives (MoLGRDC), Ministry of Home Affairs and various city corporations. And when it comes to coordination, these institutions, despite their distinct mandates and responsibilities, often end up hitting the wall.

On top of that, there’s a whole other universe of private and non-government actors, each with their own priorities and protocols. This fragmented structure makes multisectoral collaboration not just a need, but a necessity. In this piece, we’ll dive deeper into the intricacies of this fragmented landscape and explore potential solutions to strengthen multisectoral collaboration in urban health systems.

The Actors and Stakeholders in Urban Health

According to the Multisectoral Action Plan (2018-2025), ‘MoHFW should have clear priority-implementing partners from other sectors, in particular: Prime Minister’s Office, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Commerce, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Food, Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Housing and Public Works, Ministry of Industries, Ministry of Information, Ministry of Land, Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperatives, Ministry of Primary and Mass Education, Ministry of Religious Affairs, Ministry of Road Transport and Bridges, Ministry of Women and Children Affairs, Ministry of Youths and Sports, National Board of Revenue, Bangladesh Standards and Testing Institute (BSTI), opinion leaders, civil society, religious leaders, academia and research institutes, development partners and NGOs. This inclusive approach can be enhanced need using existing linkages and forming a NCD stakeholder consortium.’[1]

The Action Plan, developed by the Noncommunicable Disease Control Programme under Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), also stresses that ‘Health-in-all policies’ require successful placement of the agenda in other sectors that can be brought on board, when they are convinced that the linkages of their programme to health are clear. Although ministries and other sectors are addressing key health-related issues, further work remains to bring together different ministries to incorporate multisectoral engagement on a common platform for improving health to address SDGs and achieve UHC. Effective inter-ministerial coordination is required for the implementation of interdepartmental and intra-departmental activities.[2]

According to the Urban Health Survey (2021), approximately 90% of communities, including both slum and non‑slum areas in city corporations as well as municipalities, had a health facility located within two kilometers.[3][4] Yet, proximity hasn’t translated into effective utilization. The Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2022 revealed that urban health‑seeking was fragmented: 44.6 % sought care from pharmacies/compounders, 13.0 % from qualified doctors’ chambers, 11.7 % from non‑qualified providers, and only 13.1 % used private clinics or hospitals.[5]

The Local Government Division (LGD) delivers services through the Urban Primary Health Care Services Delivery Project, contracting NGOs across most city corporations. Some city corporations also run their own facilities, for instance; Dhaka South’s Mohanagar General and Shishu Hospitals. Other than that, NGOs such as Smiling Sun, Marie Stopes, National Health Network, etc. provide both curative and preventive care across urban centers, often through networks.

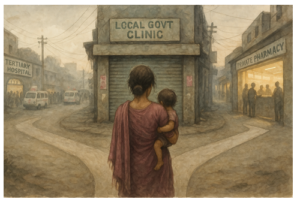

Bangladesh: A Unique Case of Lack of Synergies

As mentioned earlier, urban primary health care (PHC) officially falls under the responsibility of the MoLGRDC, which operates separately from the MoHFW, though there are formal lines of coordination. However, the MoLGRDC has acknowledged its limited capacity to build a robust urban PHC system or oversee the private health sector, which now serves as the primary provider of urban health services. Apart from some outpatient care offered through government hospitals, dispensaries, and school-based clinics, government PHC services are largely absent in urban areas. This vacuum has been rapidly filled by the private sector, especially through a vast number of drug stores and increased patient reliance on tertiary hospitals.

Public health experts have long raised concerns about this issue. At a recent roundtable hosted by the ARK Foundation—a non-profit organization working in Bangladesh’s public health sector—leading figures from the country’s health sector criticized the MoHFW for its lack of accountability. Despite 32% of the population now living in urban areas, they described the delegation of urban health responsibilities to the MoLGRDC as a ‘crime’.

Due to the absence of MoHFW’s leadership and guidance, patients are often unaware of where to seek primary care, leading many to head straight to tertiary hospitals—further straining the system. This lack of clarity in service delivery also results in higher financial burdens for patients. With limited access to affordable, quality PHC, people often rely on expensive or informal services, contributing to Bangladesh’s alarmingly high out-of-pocket health expenditure, which according to a report published in the BSS News, currently stands at 73%.[6]

There have been initiatives to deliver urban primary health services through public–private partnerships, most notably through the Urban Primary Health Care Project, which started in 1998 with funding from the Asian Development Bank (ADB). According to ADB’s website, the project has expanded over 45 partnership areas across 11 city corporations and 13 municipalities. While The project continued provision of PHC through contracting-out NGOs, civil society organizations (CSOs), private sector, etc. with a view to building healthcare facilities where such facilities were absent.[7]

The MoHFW is somewhat aware of the lack of quality and affordable PHC in urban areas, especially for the growing number of underprivileged city dwellers. In its Third Health, Population and Nutrition Sector Development Programme (HPNSDP), the government said it would focus more on providing maternal, newborn, and child health services in urban slums through a separate plan. One of the key ideas was to upgrade urban dispensaries so they could offer basic health care and also refer patients to different hospitals when needed.

However, in reality, these plans were never truly put into action. One of the main reasons the strategy didn’t work out was that the 3rd HPNSDP failed to clearly explain: i) how these services would be delivered in urban areas, ii) how the health departments (DGHS and DGFP) would work together, and iii) how they would coordinate with the Local Government Ministry, NGOs, and the private sector.

On the other hand, despite some success, the Urban Primary Health Care (UPHC) project received criticism. The Primary Health Care Systems (PRIMASYS) 2017 report noted that the project operated within a complex governance structure. It also highlighted that the implementing NGOs had limited autonomy and often had to coordinate with government agencies that may not have fully aligned with or understood their objectives.

On one hand, challenges in multisectoral collaboration continue to create bottlenecks in urban health service delivery. On the other, the private sector appears to be gradually losing interest in investing in healthcare. This concern was raised by a discussant during a roundtable hosted by the ARK Foundation, where the role of the private sector in health system development was discussed. He pointed out that, unlike other sectors where tax exemptions are more common, there are limited incentives for private investment in health. He also noted that the oligopolistic nature of the healthcare market, dominated by a few key players, discourages foreign investment and limits transparency.

Recommendations: Toward a Pragmatic Multisectoral Approach

To address these structural bottlenecks and foster more effective urban health system governance, we propose the following actionable recommendations:

- Operationalize the Multisectoral Action Plan

- Prioritize and implement existing proposals under Bangladesh’s Multisectoral Action Plan for NCDs at national and local levels

- Update the action plan to explicitly include urban health coordination as a priority domain

- Establish a Pragmatic Coordination Framework

- Create an urban health coordination mechanism chaired by the Cabinet Division or Ministry of Finance, with clear mandates and authority to convene cross-ministerial collaboration

- Define Terms of Reference (ToR) and communication protocols for all involved ministries and agencies

- Reassert MoHFW’s Leadership

- Designate the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare as the lead technical body for urban PHC system development

- Reorganize the roles of MoLGRDC to focus on urban planning and logistics, with MoHFW ensuring service quality and strategic direction

- Sensitize and Engage Non-Health Ministries

- Provide structured sensitization workshops and guidance for ministries traditionally outside the health domain (such as Water & Sanitation, Roads & Highways, Justice, Women & Children Affairs, and NGO Affairs Bureau) on how their sectors intersect with urban health and NCD prevention

- Strengthen Public–Private Partnerships

- Improve transparency and efficiency in PPP models under the UPHC project

- Offer incentives for private investment in primary care and introduce a regulatory framework to prevent monopolistic practices

- Ensure Political Commitment and Accountability

- Secure political buy-in at the highest levels to mainstream multisectoral collaboration in policy planning and budget allocations

- Monitor progress through periodic joint reviews led by the Cabinet Division, with participation from civil society and development partners

Conclusion

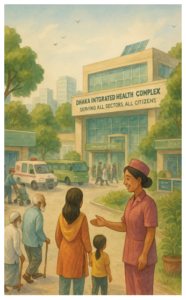

Despite various drawbacks, the MoHFW is making efforts to address persistent challenges by implementing long-term programmes such as the successive HPNSPs. The fourth edition of this programme acknowledged a critical and ongoing issue: the lack of quality and affordable primary health care for the urban poor, especially those living in slums. Recognizing that good health care is essential for all, the programme focused on three key areas to drive meaningful change: strengthening leadership and governance, improving health systems, and ensuring the delivery of better-quality health services.

A revised Essential Service Package (ESP) was introduced, covering crucial areas such as maternal, newborn, and child health, family planning, and care for both communicable and non-communicable diseases across the health system. This approach reflected a more inclusive vision, ensuring that the unique needs of urban communities were acknowledged and addressed more effectively.

With a population of over 160 million, Bangladesh’s public health sector regularly faces complex and evolving challenges. Additionally, due to the interconnected nature of development, the Health Ministry often has to respond to issues that, at first glance, may not appear to fall within the health sector’s scope. For instance, the lack of usable footpaths in cities leads to frequent pedestrian accidents, which in turn overcrowds hospitals and strains emergency services. Similarly, poor urban planning has resulted in limited access to parks and walking spaces, contributing to a sedentary lifestyle and a rise in non-communicable diseases. Consequently, the government is forced to allocate additional budgets each year to address these preventable health burdens, despite the fact that responsibilities such as building footpaths or parks lie outside the MoHFW’s mandate. Bridging this gap through better inter-sectoral coordination is essential to achieving a healthier and more livable Bangladesh. It is therefore vital that government bodies, non-government organizations, donors, and, most importantly, citizens work together toward this shared goal.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Written by: Professor Rumana Huque (Executive Director of ARK Foundation) & Abdullah M. Rafi (Research Uptake & Communication Manager, ARK Foundation)

[1] Multisectoral Action Plan for Prevention & Control of Noncommunicable Diseases (2018-2025)

[2] Multisectoral Action Plan for Prevention & Control of Noncommunicable Diseases (2018-2025)

[3] https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/teenage-pregnancy-motherhood-increased-urban-area-survey-562394

[4] National Urban Health Strategy, 2020

[5] Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2022

[6] https://www.bssnews.net/news/200361

[7] Urban Primary Health Care Services Delivery Project: Environmental Monitoring Report (July-December 2024) by Asian Development Bank